Letter from Newton to John Collins, dated 9 April 1673

Sir

Having perused Mr Gregories candid reply, I have thought good to send you these further considerations upon the differences that still are between us. And first that a well polished plate reflects at the obliquity of 45 degrees more truly then direct ones seems to me very certaine. For the flat tuberculæ or shallow valleys, such as may be the remains of scratches almost worne out will cause the least errors in the obliquest rays which fall on all sides the hill, excepting on the middle of the foreside & bacside of it, that is where the hill inclines directly towards or directly from the ray: For if the ray fall on that section of the hill, it's error is in all obliquities just double to the hill's declivity: but if it fall on any other part of the hill its error is less then double, if it be an oblique ray. & that so much the lesse, by how much the ray is obliquer; but if it be a direct ray its error is just double to the declivity & therefore greater in that case. I presume Mr Gregory, if you think it convenient to transmit this to him, will easily apprehend me.

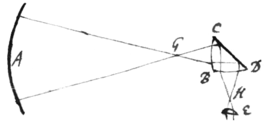

How the charge may be varied at pleasure  in my Telescope will appeare by this figure, where A represents the great concave, E the eye-glass, & BCD a Prism of glass or Crystall whose sides BC & BD are not flat but spherically convex, so that the rays which come from G the focus of the great concave A, may by the refraction of the first side BC be reduced into parallelism, & after reflection from the base CD be made by the refraction of the next side BD to converge to the focus of the eyeglass H. The Telescope being thus formed it appears how the charge may be altered by varying the distances of the glasses & speculum.

in my Telescope will appeare by this figure, where A represents the great concave, E the eye-glass, & BCD a Prism of glass or Crystall whose sides BC & BD are not flat but spherically convex, so that the rays which come from G the focus of the great concave A, may by the refraction of the first side BC be reduced into parallelism, & after reflection from the base CD be made by the refraction of the next side BD to converge to the focus of the eyeglass H. The Telescope being thus formed it appears how the charge may be altered by varying the distances of the glasses & speculum.

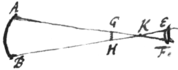

As for the objection that Mr Gregorie's Telescope will be either overcharged or have too small an angle of vision &c; I apprehend that the difference betweene us lies in limiting the aperture of the eye-glass. Mr Gregory puts it equall to that of the little concave, but I should rather determin it by this proportion: That if a middle point be taken between the eye-glass & its focus, the apertures of the eye-glasse & concave be proportionall to their distances from that point. That is suppose AB the little concave, EF the eye-glass,  GH their common focus or image, & K the meane distance between GH & EF, from the extremities of AB draw AK & BK butting on the eye-glass at F & E, & EF shall be its aperture. The reaso{n} of this limitation is that the superfluous light which comes on all sides of the speculum AB to the space GH in which the picture of the object is made, may fall besides the eye-glass. For if it should passe through it to the eye, it would exceedingly blend those parts of the picture with which tis mixed, and such are those parts of it which extend themselves beyond the lines AK, BK. As I remember I said in my former letter that the scattering light which falls on the eye-glasse will disturb the vision & this is to be understood of any straggling light which comes not from the picture, but if it come from the picture to the eye-glasse the disturbance will be much greater so as not to be allowed of. Against the first I see no very convenient remedy & against the last none but assigning a small aperture to the eye-glasse; supposing the Telescope is used in the day-time or in twy-light or to view the Moon or any Starr very neare her or near the brighter planets. And if for this reason the aperture be limitted by my rule, the angle of vision will become very small as I affirmed; For instance in that case where Mr Gregory in his Postscript puts it above 20 degrees it will be reduced to lesse then halfe a degree. Yet I confesse there is a way by which the angle of vision may be somthing inlarged but it will not be very considerably unless the eye-glass be also deeper charged{.}

GH their common focus or image, & K the meane distance between GH & EF, from the extremities of AB draw AK & BK butting on the eye-glass at F & E, & EF shall be its aperture. The reaso{n} of this limitation is that the superfluous light which comes on all sides of the speculum AB to the space GH in which the picture of the object is made, may fall besides the eye-glass. For if it should passe through it to the eye, it would exceedingly blend those parts of the picture with which tis mixed, and such are those parts of it which extend themselves beyond the lines AK, BK. As I remember I said in my former letter that the scattering light which falls on the eye-glasse will disturb the vision & this is to be understood of any straggling light which comes not from the picture, but if it come from the picture to the eye-glasse the disturbance will be much greater so as not to be allowed of. Against the first I see no very convenient remedy & against the last none but assigning a small aperture to the eye-glasse; supposing the Telescope is used in the day-time or in twy-light or to view the Moon or any Starr very neare her or near the brighter planets. And if for this reason the aperture be limitted by my rule, the angle of vision will become very small as I affirmed; For instance in that case where Mr Gregory in his Postscript puts it above 20 degrees it will be reduced to lesse then halfe a degree. Yet I confesse there is a way by which the angle of vision may be somthing inlarged but it will not be very considerably unless the eye-glass be also deeper charged{.}

Why I assign a concave with an eye-glasse to magnifie small objects (in Transactions pag. 3080) & yet an eye-glass without such a concave to magnify the image of the great concave which is equivalent to a small object, is because that image doth not require to be magnified so much as an object by a Microscope, & further because the angle of the penicill of rays which flow from any point of the small object, that the object may appear sufficiently luminous, ought to be as great as possible; and a Concave will with equall distinctness reflect the rays at a greater angle of the penicill then a lens: but in the Telescope the angles of those penicills are not so great as to transcend the limits at which an eye-glass may with sufficient distinctness refract them, and therefore in these instruments I chose to lay all the str{e}ss of magnifying upon the eye-glasses. In Microscopes also I would lay as much stress of magnifying upon the eye-glass as it is well capable of, and the excesse only upon the concave.

Concering my citation of Mr Gregory against Monsieur Cassegrain the force of it lies onely in the inference that Optiq instruments most probably according to M. Cassegrains design have been tryed by reflexion; which I think I might well infer, without having regard to the specified figure of the speculum which Mr Gregory there spake of. And therefore I think it cannot be said that I made him speake of Spherick figures where his meaning was of Hyperbolick & Elliptick ones. But if I should be so understood because I put the figure of the great concave to be sphericall wherever I specify it, I know not why I might not by way of consequence make that interpretation. For it is not probable that any man would attempt Hyperbolick & Elliptick figures of speculums untill the event of Sphericall ones had beene first tryed.

<34r>And accordingly the tryall of Mr Gregory with Mr Reive was by a sphericall figure. Which tryall although I am now satisfyed that it was made very rudely yet by the information which I had of it when I wrote the letter about M. Cassegrains design, I apprehended it to have beene made with very great diligence & curiosity as I signified in my former letter at large. And this I hope may excuse me for speaking of it in the Transactions as if it had beene tryed with more accuracy then really it was. And thus much concerning the Telescope.

The design of the burning speculum appears to me very plausible & worthy of being put in practise: What Artists may think of it I know not but the greatest difficultie in the practise that occurrs to me is to proportion the two surfaces so, that the force of both may be in the same point according to the Theory. But perhaps it is not necessary to be so curious, for it seems to me that the effect would scarce be sensibly less if both sides should be ground to the concave & gage of the same tool. I suppose you have receiv'd a letter from me sent last weeke to signify my receipt of the books you sent in Queeres &c. It comes now into my mind that when I sent Mr Pitts 4łł for Kinkhuysen he further urged a promise of some copies. When you have opportunity you will oblige me to remember him that his proposall was either 4łł absolutely or 3łł with some copies. I must joyn with Mr Gregory in admiring Mr Horrox. And this all at present from Sir

Your humble Servant

I. Newton.

Cambridge Apr 9. 1673.

< insertion from lower down the page >Sir a Friend here desires to have your

judgment in the price of Francis Niceron

his Thaumaturgus Opticus printed in Latin

at Paris A.D. 1646.